When most Americans think of the Revolutionary War, they recall names like Bunker Hill, Camden, Valley Forge, and Brandywine. But few think of Brooklyn, assuming the city suffered little during the conflict. But is that really the case? Learn about the tragedy that unfolded after the Battle of Long Island on brooklyn-yes.com.

Brooklyn’s Pivotal Role

In reality, New York—and by extension, Brooklyn—played a crucial role in the American Revolution. The largest battle of the war, involving over 30,000 soldiers on both sides—while New York City’s population stood at just 25,000—did not take place in New England or the Chesapeake, but right in Brooklyn. The Battle of Brooklyn was a devastating loss for the Americans, with over 1,500 killed, wounded, or captured.

George Washington’s secret nighttime retreat from Brooklyn to Manhattan was akin to a colonial-era Dunkirk. Much like the 1940 evacuation of British troops from Dunkirk and other beaches in western France, the Americans escaped early destruction and, battle-hardened, continued the fight.

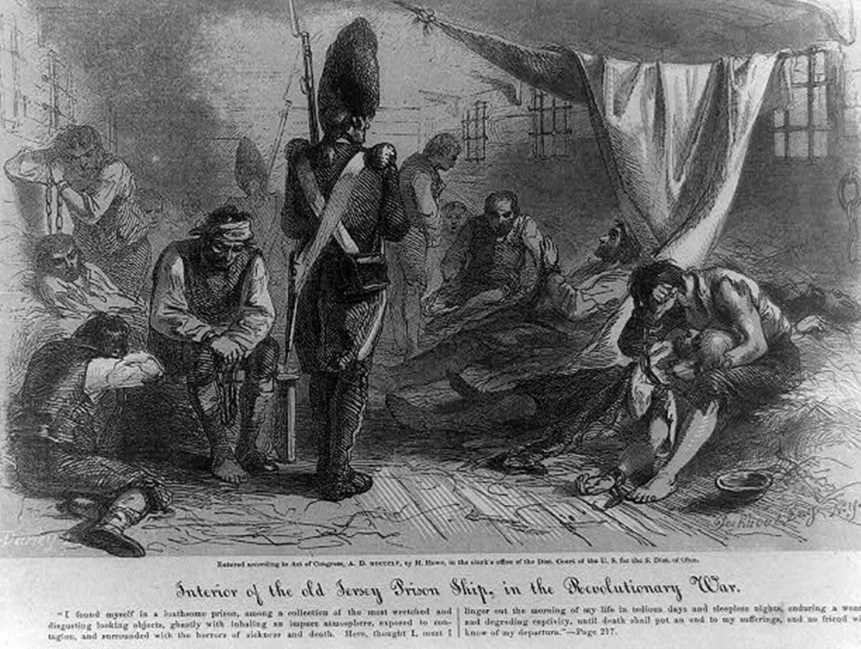

However, nothing compared to the suffering and death that occurred aboard British prison ships. In these floating wooden Bastilles moored in New York’s waters, more Americans perished than in all the battles of the Revolutionary War combined. Over 8,000 Americans died in combat between 1776 and 1783, while more than 11,000 prisoners died aboard the ships anchored or stranded in the East River. The conditions these captured soldiers and sailors endured were nothing short of inhumane.

The Horrors of Captivity

Most of the sailors who ended up in hulks were privateers, not members of the fledgling Continental Navy, which was only established in October 1775. During the war, most American naval engagements were fought by privately owned vessels operating under government-issued letters of marque, allowing them to attack British ships. The owners, captains, and crews received a share of the profits when captured ships were condemned by American authorities and resold.

The hulks were not the only notorious prisons of the war—abandoned churches, sugar refineries, and warehouses throughout the colonies also housed prisoners in appalling conditions. Many captured American soldiers and allies were even sent to prisons in England. Yet, the tales of brutality and neglect aboard British prison ships, particularly the infamous HMS Jersey, a former 60-gun warship turned floating hellhole, tell of some of the darkest realities faced by American prisoners of war.

One survivor, Robert Sheffield, escaped from one of the hulks anchored in Wallabout Bay, now the site of the Brooklyn Navy Yard. His account described unbearable heat, where over 300 prisoners were kept completely naked to stave off lice infestations. The sick were devoured alive by parasites. Their gaunt faces, haunted eyes, and desperate cries painted a harrowing picture. Some cursed and blasphemed, others wept, prayed, or clutched their hands in despair. Some wandered like ghosts, while others lay in feverish delirium. Many were already dead, their rotting corpses mixed with the filth of the ship’s hold.

The air was so foul that it was sometimes impossible to keep a lamp burning. After sundown, only one prisoner was allowed on deck to dispose of waste, leaving the interior filled with filth and stagnant bilge water.

Five to Ten Corpses Daily

Even the food was deadly. Prisoners were forced to eat moldy bread, rancid meat of questionable origin, and “soup” boiled in massive copper cauldrons using water from the East River—which, it should be noted, is not a river but a tidal strait. The result was more akin to toxic sludge than a meal.

Each day, bodies were discarded overboard from the HMS Jersey—five to ten corpses per day. Over time, thousands of decomposed remains washed up along the Brooklyn shoreline. When possible, Brooklyn residents gathered the bodies, burying as many as they could in local cemeteries. Eventually, the remains were transferred to a crypt in Fort Greene Park, about half a mile south of Wallabout Bay.

In the early 20th century, the renowned architectural firm McKim, Mead & White added a 149-foot Doric column to the crypt, topped with an eight-ton bronze brazier. A 100-foot-wide staircase was built leading up to a grand plaza above.

Many names of the thousands who died on the prison ships are known. However, no one knows for certain whose remains rest in the crypt, nor how many are truly buried there. They remain intermingled—bones and dust—sealed in blue stone chests beneath Brooklyn’s hillside terrace.